The History of Transportation on Colorado's Mountain Passes

Horse Trails, Wagon Roads, Donkeys & Gold

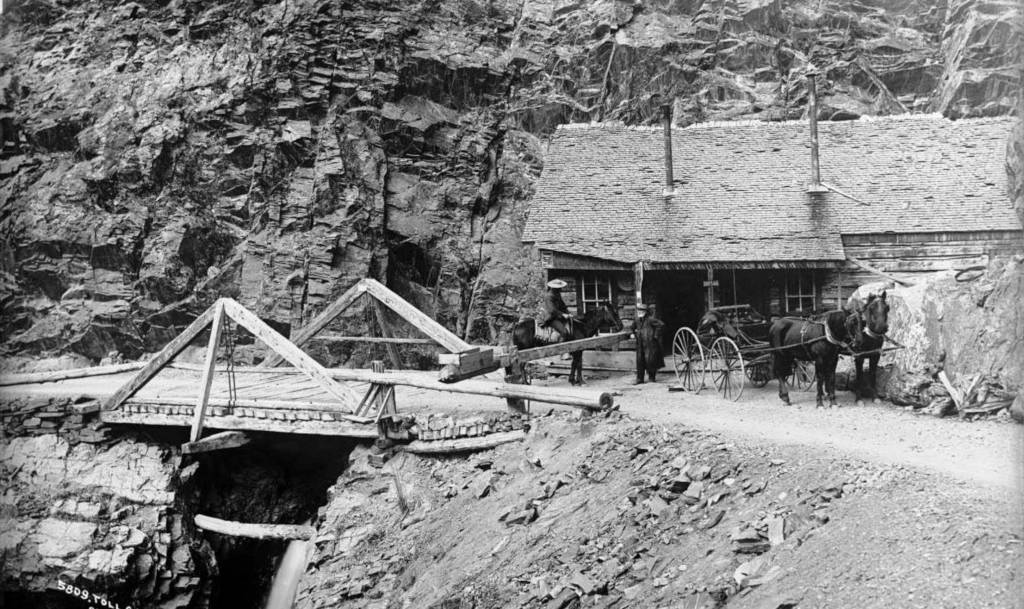

Many of Colorado’s modern mountain passes began as trails that were used by settlers and natives. The passes could be traversed on horseback and on foot. Miners would use donkeys and mules to move ore and supplies through the mountains on these trails.

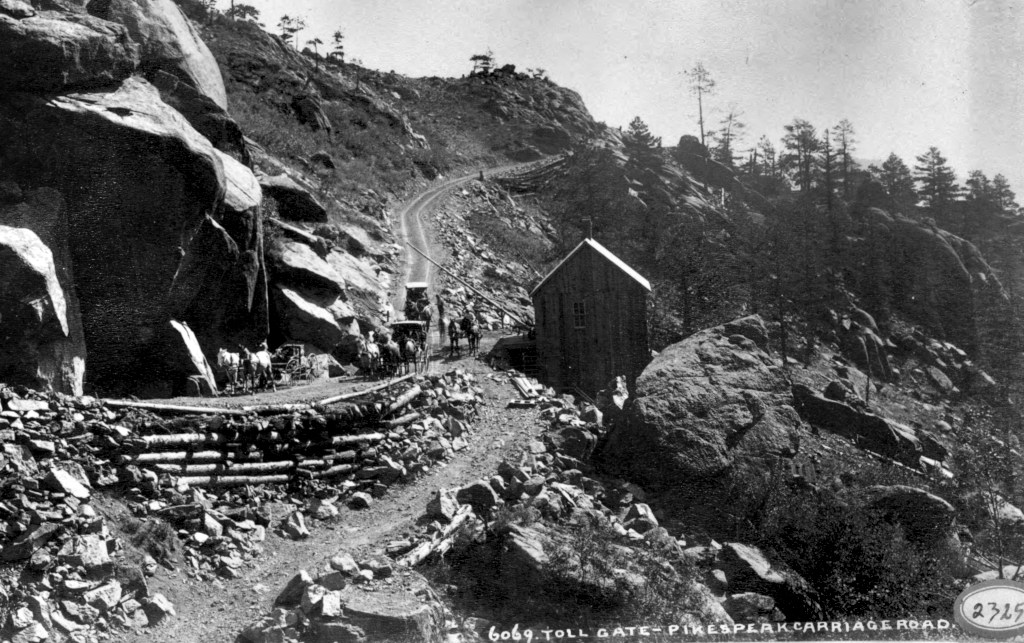

As the mining booms of the 1800s hit Colorado, many of these paths were turned into wagon roads. A lot of these wagon roads that ran deep into the mountains were built as toll roads. They gave settlers access to the mining regions of the state, in some cases, acting as the forerunners to the railroads that would follow.

Examples of old toll roads that are now modern highways include Loveland Pass, Berthoud Pass, Independence Pass, and the Silverton and Ouray Toll Road. These were all toll roads at one point in the 1800s.

The gold and silver rushes would pass, and towards the end of the 1800s many of the mountain passes fell into disrepair. Some mining towns would turn into ghost towns, leaving their mountain roads behind. In other cases, railroads took the place of the freighting routes, and the toll roads were no longer sustainable. Many of these old roads are now dirt roads that are used by jeeps for recreation. Others turned into modern highways that still act as key transportation arteries through the mountains today.

Otto Mears Builds it All and Then Runs for His Life

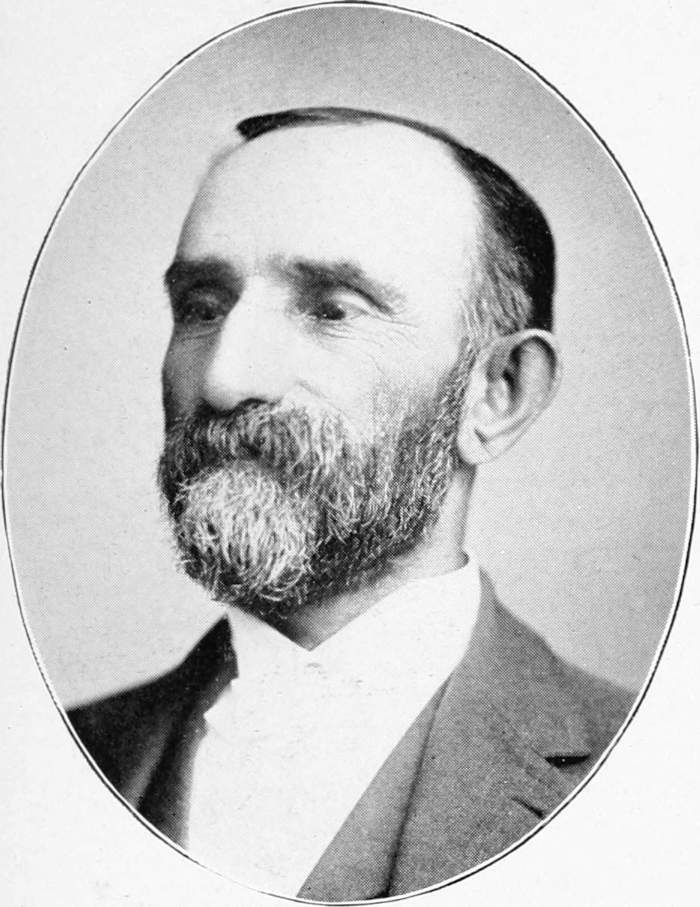

Otto Mears was an innovative engineer who built railroads and highways throughout Colorado’s mountains. One of his more well-known accomplishments was building the Silverton and Ouray Toll Road in the San Juan Mountains in 1884. This would later be known as the Million Dollar Highway.

Otto Mears was an innovative engineer who built railroads and highways throughout Colorado’s mountains. One of his more well-known accomplishments was building the Silverton and Ouray Toll Road in the San Juan Mountains in 1884. This would later be known as the Million Dollar Highway.

Otto also negotiated with Chief Ouray on behalf of the Government. He befriended the chief, as Otto was one of the few white people in this area who could speak the Ute language. Mears had a contract with the government to supply food to the Utes, and this helped him to deepen his relationship with Chief Ouray and the tribe. In order to get the chief to sign the Brunot Agreement in 1973, Mears suggested that the chief be given a $1,000 annual salary for the next 10 years.1

This agreement took a significant portion of land away from the Utes. Having felt betrayed, members of the Ute tribe became so angry that they forced Otto Mears to run for his life at one point (this is probably a mix of truth and legend).2

Pay to Play - The Early Toll Road Era

Some mountain roads were built with money from the local towns and counties, but many of the most important mountain passes were built by private companies as toll roads.

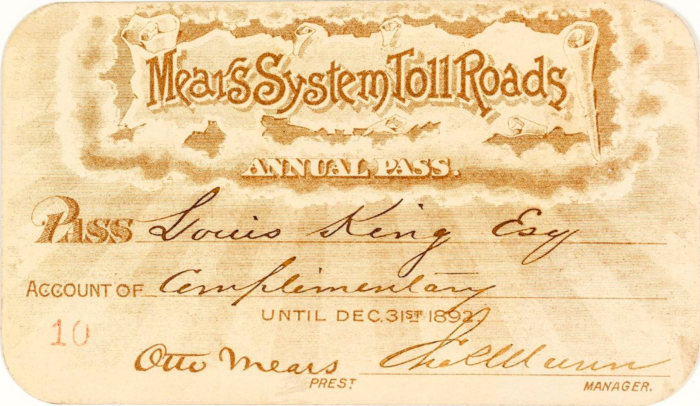

Otto Mears built several toll roads in addition to the Silverton and Ouray Toll Road, and if you wanted to haul ore out of the mountains on one of his wagon roads, you were going to have to pay. Toll amounts were not that different than what you might pay today on a modern toll road. However, since this was in the 1800s, this would have been considered a much more significant price at the time.

You could even buy an annual pass that was valid on all of Otto Mears’ toll roads. The example is a real pass, currently held by the Library of Congress.

How much did it cost to use Colorado’s toll roads in the 1800s?

Two of the most expensive toll roads to drive a wagon on were the Silverton and Ouray Toll Road, and the toll road over Berthoud Pass. Mears was charging $5 for a wagon, and $1 for a single horse to use the Silverton and Ouray road. In the 1870s, a wagon could make a round trip over Berthoud Pass and back for about $7.

Not all toll roads were this expensive. Just as Loveland Ski Area is one of the more budget-friendly ski areas now, Loveland Pass was one of the more budget-friendly toll roads. The cost for a wagon was only $1, while horses and donkeys could pass for only $.15/each.

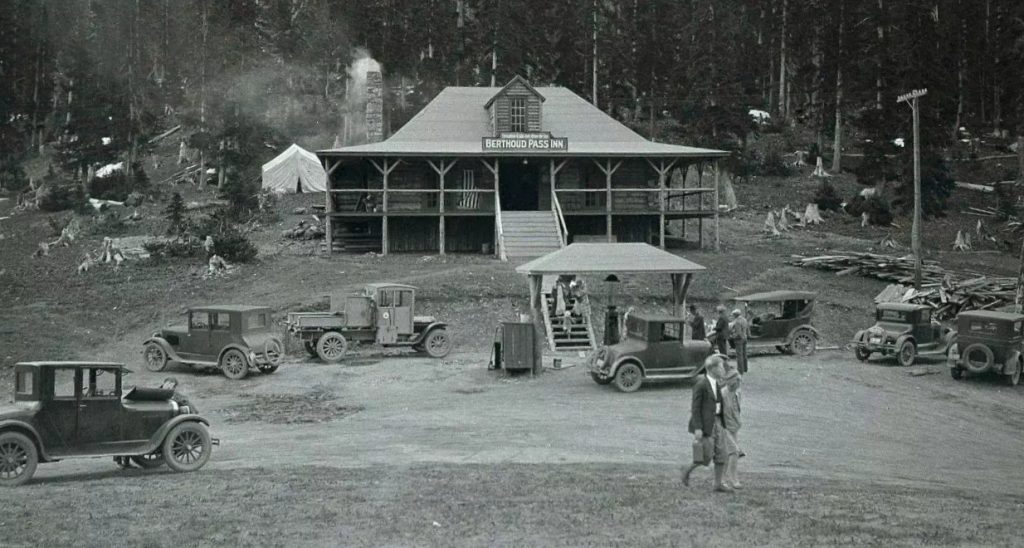

The Auto Boom of the Early 1900s

Cars began arriving in Denver almost exactly at the turn of the century. They were called horseless carriages at the time, and their presence was controversial. Electric cars were being built out of Denver by 1907, and the number of automobiles on the road in Colorado would begin to grow exponentially from here. There were approximately 90 vehicles in Denver in 1900, 800 by 1905, and more than 4,000 by 1910.3

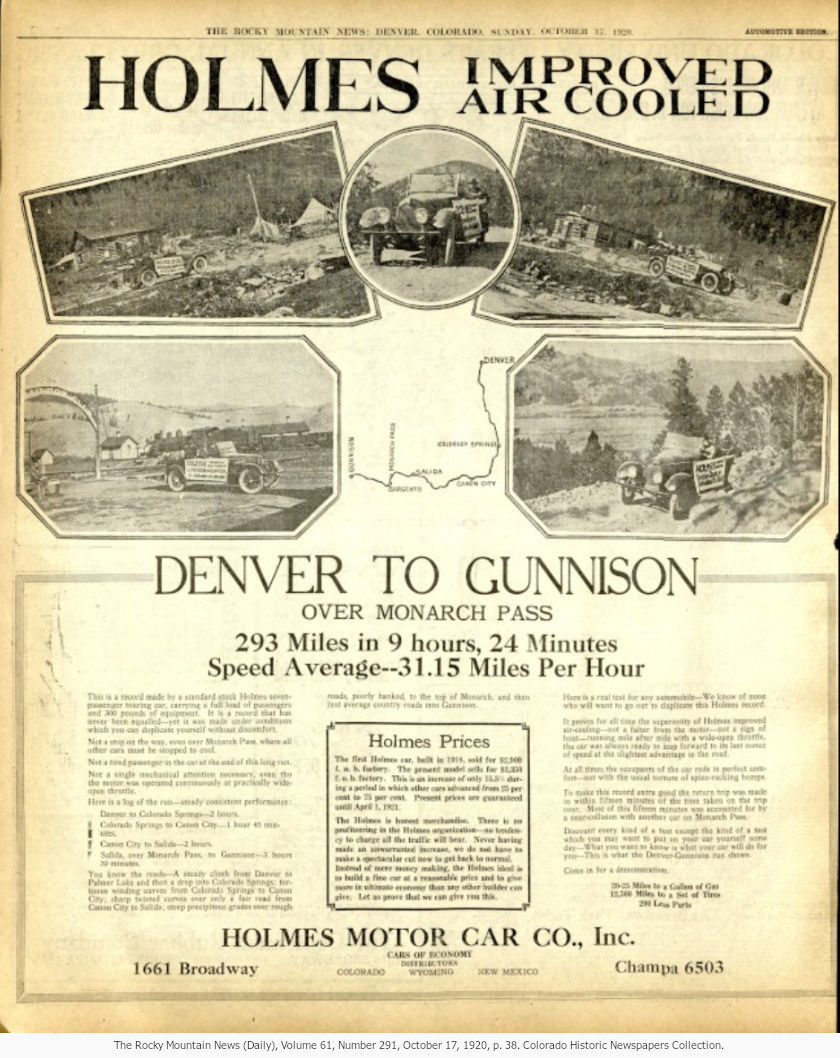

This newspaper spread is from the Rocky Mountain News in 1920. Automobile travel into the mountains was surging at this point, and a lot of Colorado’s mountain passes over the divide were being improved.

Read the newspaper spread in full resolution here on Coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

Some mountain passes would be revitalized when automobiles gained popularity in the early 1900s. Some became even more popular 100 years ago than they are today, such as Hoosier Pass. Loveland Pass had mostly fallen into disrepair after the turn of the century. While it was still passable, Hoosier Pass was the preferred route to Breckenridge during the first 20-30 years of the 1900s. A modern, improved dirt highway was completed over Loveland Pass in 1932. Meanwhile, Berthoud Pass has been among the most traveled routes throughout the last 150 years.

As wagon roads became auto roads, contracts were awarded left and right for grading and road maintenance. The roads that were being built were crude dirt roads, but everyone knew that quality roads were the key to commerce. Improving the highways through the Colorado mountains would be a priority for local governments throughout the first half of the 20th century.

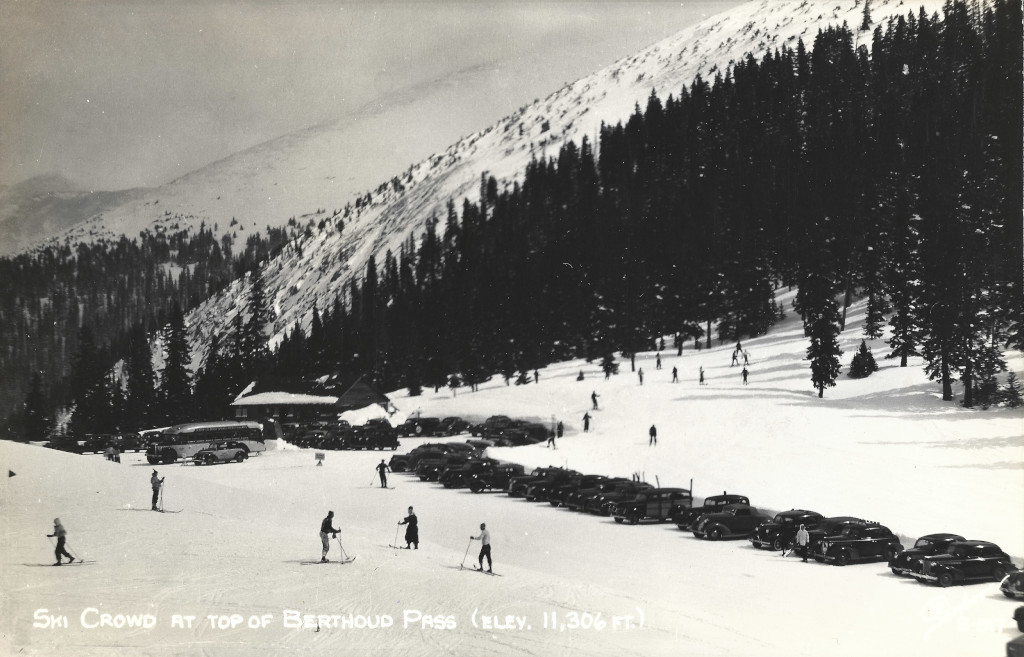

Recreation was also a driver of highway development into the mountains. It was estimated that 50,000 people skied on Berthoud Pass in the winter of 1937-’38. This was an increase of 20k skiers vs the prior year.4

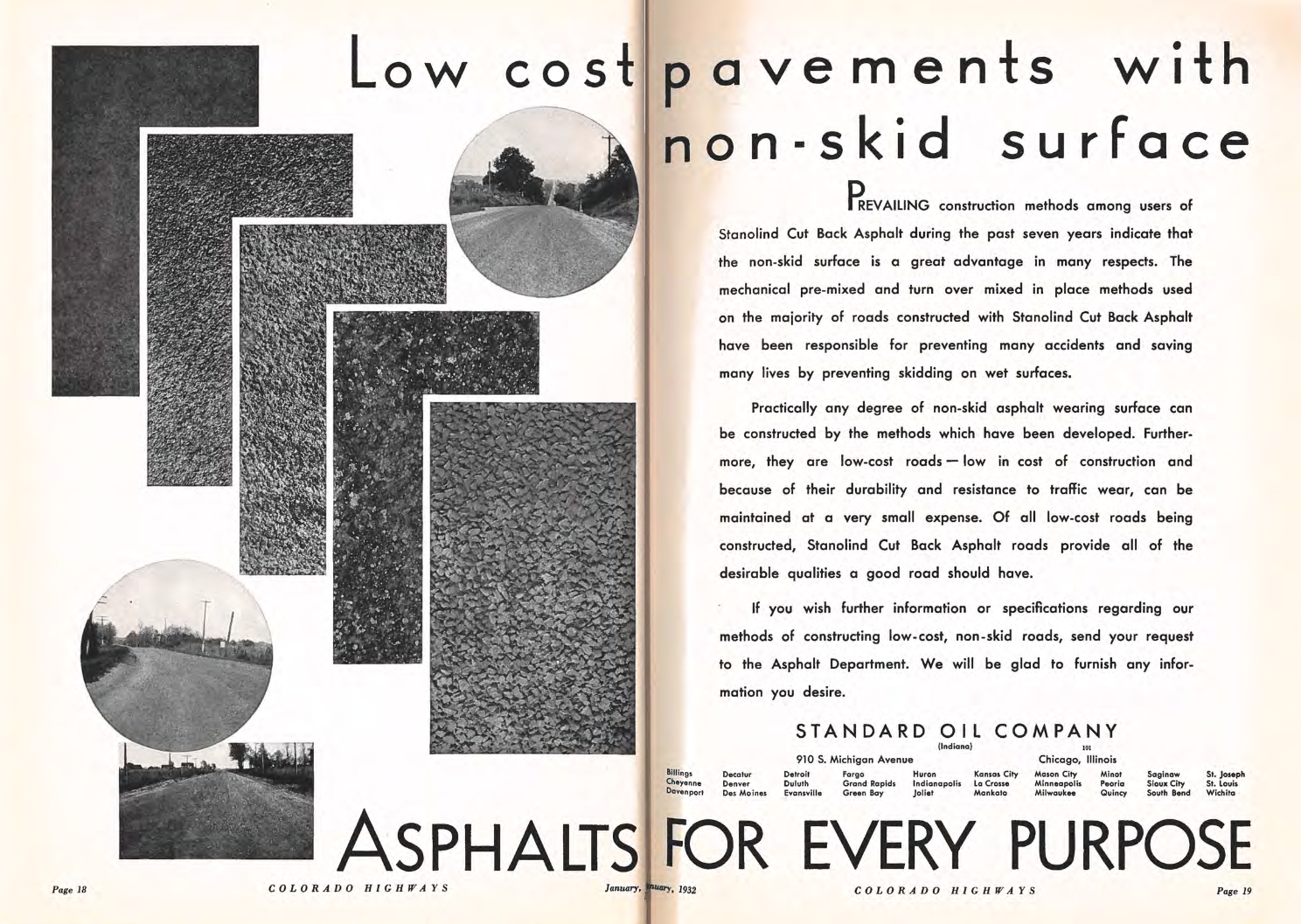

From Dirt Roads to Oiling and Paving

The early wagon roads were all dirt roads, and many of them were rough to travel on. Some mountain passes had sections with grades as high as 30% (like Hoosier Pass).

What was oiling? Oiling was not paving in the early 1900s. Oiling was a surface coating that was applied to dirt roads in order to try and keep down dust. This was used in the first half of the 20th century on many of Colorado’s mountain roads.

Into the 1930’s and 40’s, the term “oiling” was still used, but it now also referred to a paving process that resulted in a hard surface. For example, in 1939 Monarch Pass was “oiled” but the result was a hard paved surface. Sometimes, oiling was just akin to modern asphalt.

The advertisement below comes from the Colorado Highways publication in 1932. This shows some of the paving options at the time, and points out that adding grip was among the innovations achieved by the new forms of asphalt.

As cars became more popular during the 1910s and into the 20s, auto travel into the mountains became its own recreational activity. This came alongside of massive improvements to the mountain highways which were primarily driven by commerce.

Trail Ridge Road Paves the Way

Trail Ridge Road is the main scenic byway highlight of Rocky Mountain National Park. This roadway was an engineering marvel at the time it was built. This was the highest continuously paved road in the country, and it still is to this day. Trail Ridge Road travels through high alpine tundra with a layer of permafrost, and this made road construction extremely difficult.

Construction on Trail Ridge Road began in 1929 and was completed in 1935, although the new road opened before that. This replaced Fall River Road.

Monarch Pass is Paved Soon After

Paving of the new Monarch Pass was completed in 1940. The process to pave Monarch Pass was much simpler than Trail Ridge Road, and you can see a difference in the appearance of the road surfaces as well. Monarch Pass was paved with an oiling process.

Rotary Snowplows Rule the Day

The first rotary snowplow that was used on the roads of Colorado was an adaptation of the same design that had been used on railroads for many years. The Colorado State Highway Commission built their own custom rotary snowplow in 1922, and another custom rotary snowplow was designed by a lumberjack named Kid Hoover in 1924.

Rotary snowplows would soon be deployed to mountain passes across the state in the 1920s, but none of the difficult mountain passes over the Continental Divide were able to stay open year-round for cars until the 1930s. By this time, the plow designs being used for the deepest snow were an auger-style rotary plow that was similar to a modern snowblower’s design. A Snowgo was used to open Trail Ridge Road in Rocky Mountain National Park for many years, and is now in the National Register of Historic Places. Read about the History of Rotary Snowplows in Colorado here.

By the 1950s, almost all of the major paved mountain passes through the mountains were staying open year-round.

Thawing Out...

Even with the rotary snowplows ready to go, routes like Trail Ridge Road through Rocky Mountain National Park are still not open during the winters. Independence Pass is a major route into Aspen, and this is also closed for the winters. Cottonwood Pass also joins the list alongside of these two.

The image below shows what it looks like in the spring when Trail Ridge Rd. is getting ready to open.

What a difference a day makes

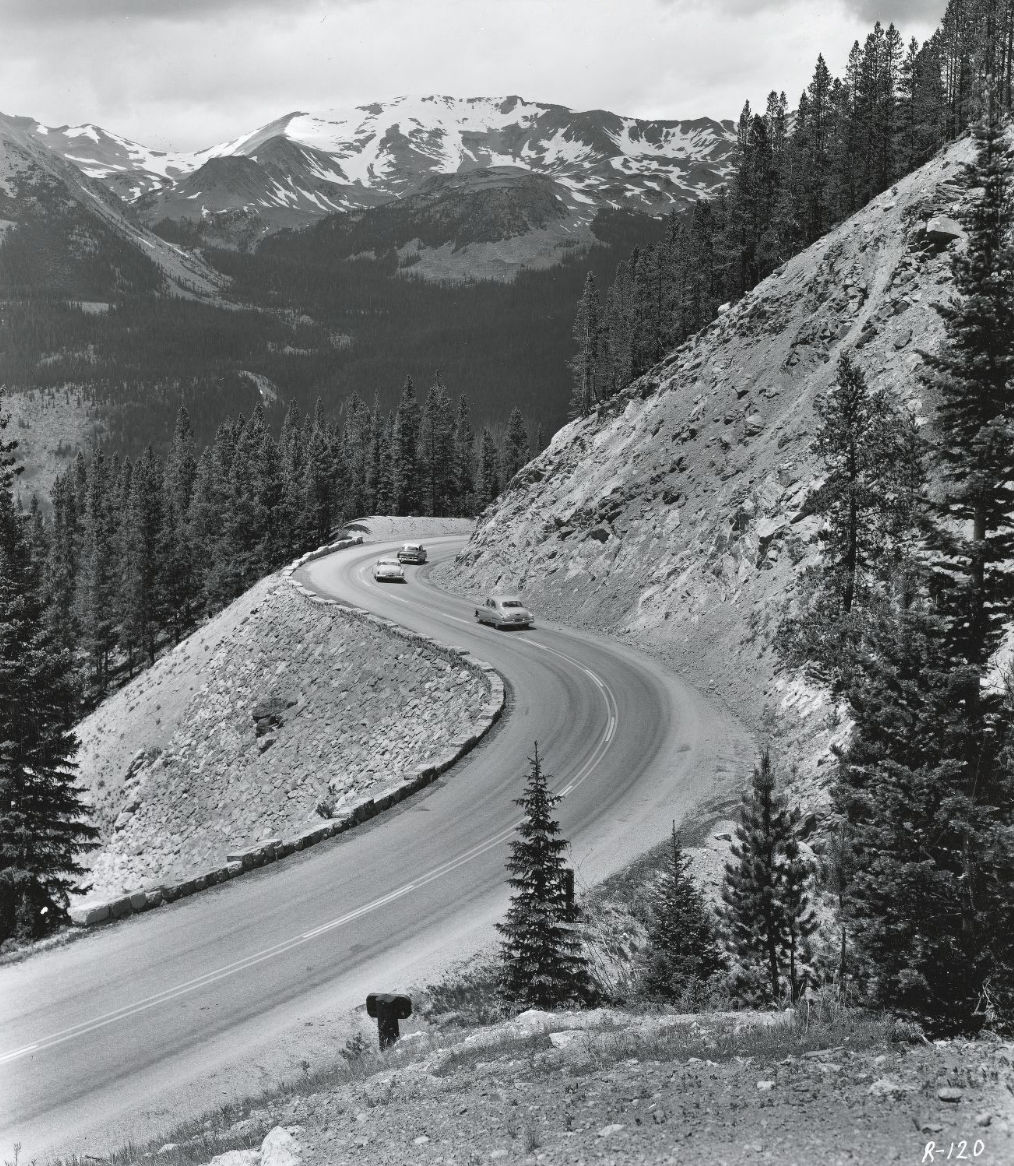

Highway 6 was the predecessor to I-70 through much of the state. The two highways are seen side by side, heading into the Rocky Mountains below. This trio of photos looks west just after entering the mountains, west of Denver.

US Highway 6 has always gone over Loveland Pass. Even as the main route over the divide into Summit County, this part of the highway was not paved until 1950. The photo below from 1952 shows a high altitude research center that was built in the summit area around the time the pass was paved.

The Boring Part...

The Eisenhower Tunnel first opened in 1973. The second tunnel bore, the Johnson Memorial Tunnel, was completed in 1979.

This tunnel, officially known as the Eisenhower–Edwin C. Johnson Memorial Tunnel, allows motorists to bypass Highway 6 over Loveland Pass, saving approx. 30 minutes off of the commute into Summit County. Loveland Pass is still heavily used today. That is the only access road for the Arapahoe Basin Ski Area, and it is also the only route that can be used by trucks carrying hazardous waste material to the other side of the Continental Divide. If the pass is closed, the tunnel will shut down once per hour to allow hazardous material trucks to pass through.

The Continental Divide. Conquering the divide by wagon, by railroad, and by automobile has been a transportation goal for centuries now. View the Continental Divide Guide.

Milestone Dates in the Mountains

1874 – The first wagon was driven over Berthoud Pass on Nov. 18, 1874.

1884 – The Ouray Silverton Toll Road opened in 1884. This would later become the Million Dollar Highway.

1879 – A toll road for wagons was built over Loveland Pass in 1879. A modern dirt highway for cars over this pass was completed in 1932. Read the full In-Depth Loveland Pass History.

1916 – The first Pikes Peak International Hill Climb was held in 1916. Rea Lentz from Seattle wins $1,000 for first prize, with a time of 22 minutes and 55.6 seconds.

1932-’33 – Berthoud Pass stayed open through the winter for the first time since the automotive age began.

1950 – Loveland Pass was paved. While this pass had flourished during the 1800s, it was nearly abandoned at the turn of the century. As the auto boom took off, Berthoud Pass and Hoosier Pass received the funding and became preferred routes into the mountains, while Loveland Pass remained mostly in disrepair.

1967 – Independence Pass was paved.

1973 – Eisenhower tunnel opening. The first of two bores would open with one lane going in each direction. The second tunnel bore opened in 1979.

1992 – Interstate 70 through Glenwood Canyon is completed. Construction of I-70 through the canyon began in 1981 and continued through 1992.

Credits & References

Images Credits: Coloradotopia Archives, Denver Public Library Special Collections [X-8506] [Z-7168] [Z-7169] [OP-20765] [RMN-041-4451] [Z-108] | More info

- "Brunot Agreement." Colorado Encyclopedia. Accessed November 3, 2024. https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/brunot-agreement.

- Colorado Experience: Million Dollar Highway. Rocky Mountain Public Media Inc., 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J6xq3DMjvrA.

- Beaghler, Steven Llewellyn. "The Automobile in Denver: 1895-1910." Master’s thesis, University of Colorado Denver, 2021, p. 67. Retrieved 2024 from https://digital.auraria.edu/work/ns/bff0a5e1-7bf6-4b22-ab9f-e4400a4d5a42.

- The Aspen Times (weekly), June 1, 1939, p. 1.