1923

1923 – An inspection trip was planned in July of 2023 to decide how to spend the $20,000. The NEW road, this time built by the state instead of by volunteers, was now planned to be a part of the Holy Cross Trail. Before the survey trip, the preliminary plan was to create a 10-foot wide road with turnouts to allow for passing of traffic. This could be widened later.

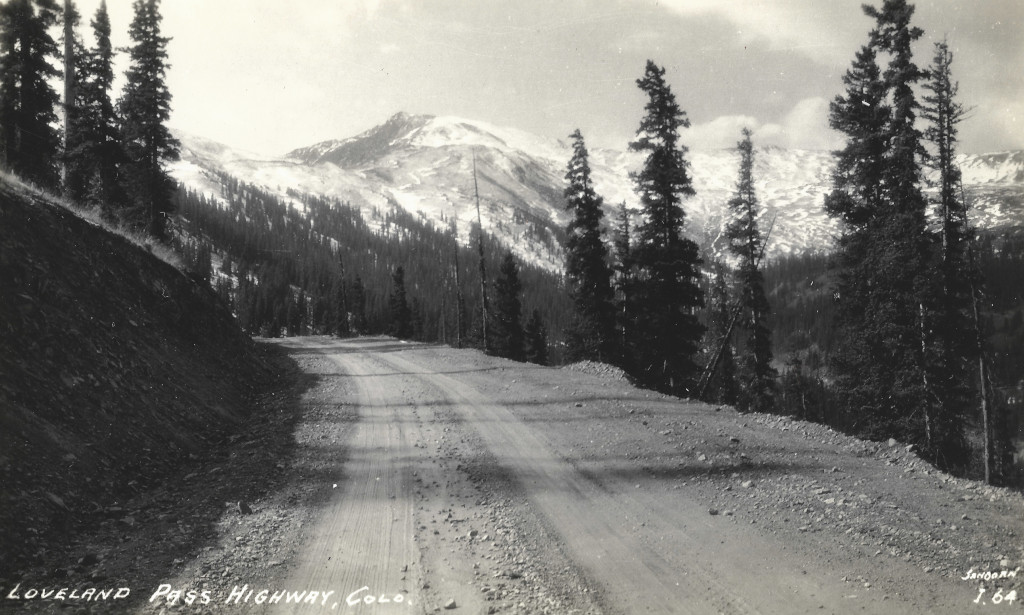

Further plans for this next version of the road evolved to include a 14-foot wide road.

Work on the pass began in July. Roy Mooney was in charge of construction. The State of Colorado would now do the work, having contracted R.W. McQueary for his men. McQueary had been building roads in Colorado since at least as far back as 1908, before the auto boom in Colorado really even began. He and his crews had a good reputation. They had already built Fall River Road in Rocky Mountain National Park.

The road was reported to be finished to within two miles of the top of Loveland Pass in the fall of 1923.

The roadway that was being built was now being extended to 14 feet wide, wide enough for two cars to pass each other at any point. This would not remain the case, because reports about the road in later years were that much of it was still only 1 lane.

A report to the highway department in November 1923 states that 3.5 miles of Loveland Pass were constructed. Surveying had begun on 4 additional miles of road which would be completed before the next summer. It was estimated that an additional 12 miles on top of that would eventually also be needed.

1924

No money was appropriated to finish construction in 1924.

The $20,000 appropriated in 1922 was secured by E.E. Sommers, a member of the State Highway Board. This was under Governor Shoup. Governor Sweet was elected in 1923, and he effectively stopped the work by not appropriating any funds in 1924.

1925

Another $20,000 was appropriated by the highway department for 1925, for the purpose of bringing the two ends closer together at the top of Loveland Pass.

A surveying crew led by Leland Boatright headed for Loveland Pass in June of 1925. They were expected to be there for the summer. The Georgetown Courier reported that road work began in July.

A contract for two more miles of road construction was initially awarded by the State Highway Board in October. However, Governor Morley refused to award the contract, saying the bids were too high. The lowest bid was $15,542 and the state’s engineer had estimated the project at $14,750. The governor began to propose using convicts to do the work in late October.

It was announced in December that a force of convicts would indeed be used to help build the highway.

1926

$30,000 was appropriated for the Holy Cross Trail in 1926, including funds for Loveland Pass, but it is not determined yet how much of that would be put towards the pass immediately.

A team of 50 convicts from the state penitentiary in Cañon City started work on the pass in July 1926.

One week after setting up the work camp for them, it was reported by the Rocky Mountain News that there were 35 convicts working on the pass, and two of them had stolen an automobile which had later been seen heading over Berthoud Pass.

1927

Luke Smith wins a contract with a bid of $73,280 to complete 5.5 miles of road on the eastern side of Loveland Pass. Only $40k was currently available. He would begin work and plan to complete the rest later when funds were available.

The number of workers needed on Loveland Pass in 1927 was such that it caused a shortage of miners in Silver Plume. Work on the pass this year continued until Dec. 2nd.

1928

L.D. Blauvelt, head of the State Highway Commission, said there would be $58k allotted to the pass in 1928. This would complete the pass to the top. It would be extended all of the way down to Dillon on the west side the next year.

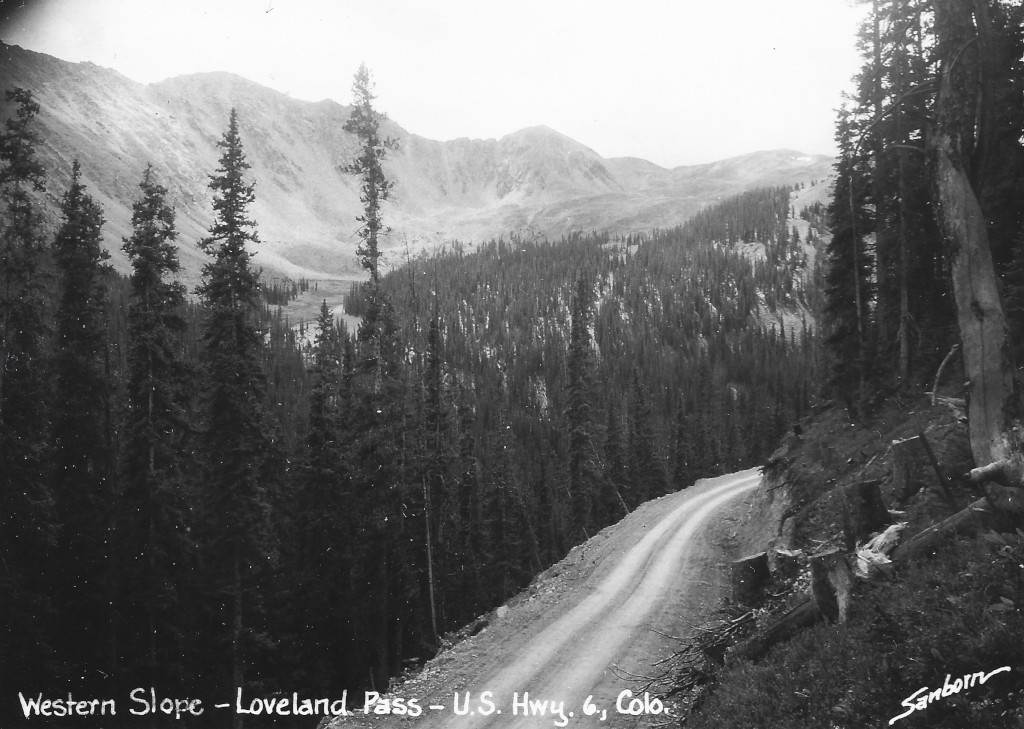

By summer of 1928, the modern dirt highway over the pass was still only completed to within 2 miles of the top. Progress would fall short of reaching the summit in 1928.